I spoke with Tadhg Devlin – a Merseyside-based photographer, about his dementia projects, his practice of socially engaged photography and his collaborative projects. Find his incredible work on his Instagram and as well as on his Website.

Sara – Hi Tadhg! Lovely to meet you. I have been following your work for a while. I found you through Open Eye Gallery but got my attention with your Dementia projects, they look amazing. I am working with people living with dementia as well and I really appreciated your perspective of showing people living with dementia and their carers.

Tadhg – Lovely to meet you too! Thank you! When I started working on the experience of people living with dementia, I didn’t know anything about dementia. I spent quite a long time focusing on people living with dementia, I started my initial project Life Beyond Diagnosis in 2016. In long-term projects, you get to know the people really well. Socially engaged practice is often conflicting in how involved you get and then the guilt when the work comes to an end and then you stay in contact with people but how much do you stay in contact? It’s difficult because the more you speak to them the more you understand and that’s why the project took a long time. The Amelia Project was different. It took so long to initially meet someone and get in contact with somebody.

I think I got involved because of NHS Mersey Care and their approach. There are cuts all the time and you can see it in social care that every action and funding is like tiny drops. But you see the amazing people working in care who make a big difference to people and their organisations. Jill and Sarah at Mersey Care put together different groups of people living with early-onset dementia. They would start running them and then more people would join the groups. That’s a pretty amazing approach from one or two individuals, being so proactive. Especially at the point when the Alzheimer’s Society moved out of Liverpool, meaning that we couldn’t continue without their money and support. So, one of the people I worked with, Roy, took over the meetings and would host them. Meetings like these are really important for the social element of staying active and keeping your mind active as well as your body. I went along to different meetings every week or so and photographed the participants. But there weren’t massive numbers, so they had to cut the funding. I’m sure you experienced it.

Sara – Yes actually, I have. When I started my job in February 2022, working for the Living Brands Programme at the Museum of Brands, we lost all our activity providers and care homes contacts due to COVID and restrictions. We had great partnerships previously. I started with one care home in February, and by May we managed to build it back up to 10-15 care homes and sessions a month. So, I understand what you are talking about.

Tell me how you got into working on these projects and about your practice!

Tadhg – There are discussions in photography around the origins of documentary photography (which I was initially interested in) trying to raise awareness around different issues and document situations. And there are ongoing discussions about whether it actually has any effect and does it change anything at all. You can be cynical and say no it doesn’t, while other people may think that even if it has a small influence on a number of people then that’s positive. I studied Art initially in Dublin and then got interested in Photography and applied to colleges in the UK because there weren’t any in Ireland at the time. So, I applied to Edinburgh to do an HND in Falmouth, Cornwall. I was trying a bit of portraiture, a bit of fashion and other practices and then started doing documentary photography and realised I was very intrigued by it. From my second year onwards, I did more documentary projects. My dad is a journalist, so maybe that explains my interest, but I was interested in the documentary photojournalistic approach. I was really immersed in those projects and those projects are similar to what I’m still doing now.

There was a project that I did on Modern Fatherhood. I wasn’t from Cornwall, so it was an interesting process of speaking to people who would then speak to another, long story short I got a contact, and I went to see him and spoke to him about it. He wasn’t quite sure what I was trying to do with this project, but he agreed. He was a stay-at-home dad with 2 young children. It was a learning process for me. I talked to him about what I was trying to do and tried to show him some of his daily life through my photos. I would take pictures of him doing whatever he was doing with the two kids running around and show their routine and understanding of their daily lives. I was also trying to learn the process of photography with lights and flashes. Then I would go off and process the films and bring back the prints which made him understand what I was trying to show with this project. It’s about building up that trust element – he would see the pictures each time throughout the project and then at the end, I print up the images in big prints. So that was the first socially engaged kind of project that I did, and I realised that I was interested in different people’s lives. They were my initial interest in documentaries and finding my area of interest. And then by the end of the course I decided that I wanted to do this as my photography practice.

As the course was ending, I decided to go and work for Magnum Photos (work experience), which was a really hard agency to get into. I called them and pursued them until I got a place doing work experience. I moved to London and started the internship just after finishing my course and worked for Magnum for a year and a half. It was incredible, but also quite hard going to an internationally renowned agency. I learned an awful lot about the industry: how people go out and shoot different projects, how they get conditions and survive, but also how difficult it is to sell your stories, especially if it’s not about a major conflict somewhere around the world. I’d be working on projects and trying to sell these stories that I would go off and do. We weren’t paid very much at all, but part of the internship’s deal was that you get a certain amount of money at the end of the year, and you could go off and do a project you wanted.

I went off to the US-Mexican border. And I was thinking about things that we would be able to sell. So rather than a project about Mexicans going into America, I was looking at Americans crossing the border into Mexico at the US-Mexican border. Later I realised, I’m not interested in this ‘sellable’ mentality in my practice. But during this project, I remember meeting this American guy, and he heard I was Irish. And he asked these three quick questions that made me think about Ireland because he said, ‘Is Ireland really green?’, ‘Do you drink like a fish?’ ‘And are you an active member of the IRA?’ Three cliches of Ireland, but that’s how Ireland is portrayed. A few years later I started this project about Ireland and how it changed called Fifth Province. I was working as a picture researcher, assisting people and I’d also shoot my own work. I started doing more freelance work and this was when I was asked those Ireland questions. I thought Ireland had changed quite a lot and was going through this ‘Celtic Tiger’ era during the late 90s. I was thinking about this idea of how things change once you leave; lots of people who stay own the country and sometimes your country changes and then you go back, and you want it to be like when you left. I changed my approach and started photographing Ireland and how my perception of Ireland changed.

Then I moved to the Northwest of England in 2011/12 and started doing projects and lecturing work. If you have an income from lecturing, the work that you’re doing doesn’t have to sell and that changes the reason you’re making work. Around this time, I met Sarah Fisher at Open Eye Gallery. I was looking at communities and at one point in 2015/16, she rang me up and asked me if I was interested in doing a project working with people living with dementia (Life Beyond Diagnosis). I didn’t really know anything about dementia. I had doubts and was unsure how I could do this project. But I was also ready to change my practice and perspective and to learn something new. There weren’t many people doing socially engaged practice in photography. And so, Sarah thought that this could be a bigger project. I was one of the first people who was commissioned by Open Eye Gallery to work on this project working with people living with dementia.

Sara – How did you end up with socially engaged practice? Where did you learn it?

Tadhg – There are all these discussions about socially engaged practice, and to be honest, people have been working that way for years since the 70s but without the label.

There are some amazing inspiring people and groups around. Hackney flashers in London for example. It’s a group of female photographers, writers, and poets, and they did a project ‘Who’s holding the baby’ looking at aspects of childcare. It was on show in Birmingham about six, or seven years ago, and that’s when I first saw it. There’s another photographer, Jo Spence, who is involved in socially engaged practice as a photo therapist and cultural worker. Susan Meiselas has been working in a socially engaged way since the early 1970s. Also, Jim Goldberg would work on long-term collaborative projects with neglected or ignored communities. An article (then book) written by Susan Meiselas and Wendy Ewald called Collaboration has highlighted socially engaged/participatory photography projects and definitely influenced me.

These practices and ideas have been around for a long time but were never called socially engaged. I feel like going from documentary photography to socially engaged practice is not that big of a jump. I suppose the difference between other work I was doing, and the more socially engaged, is that it takes longer. It’s more engaged and immersed with the person. There’s a trust that develops over time. To get a real understanding of the person or to try and get a real understanding of their personal situation. I think that was a big thing when I started doing the work with a group of people living with dementia in Liverpool.

At that point, I knew little of dementia from what I read about it. I was wondering ‘How is this going to go?’ and ‘What is it going to be like?’ and I felt ignorant about the topic as I only read stereotypical ways people living with dementia are portrayed. And then I turned up at the gallery and met Roy, one of the participants who has Lewy body dementia. There are glass panels around the gallery, and he’d walked into one of them five minutes before, and so he was really quite disorientated. Also, the gallery was locked because we were both early. Then when we managed to go in, he was telling me about seeing the Beatles in Liverpool and we had this really lively conversation that was really funny. I was driving away thinking that was bizarre because it was nothing like how I expected it to go. It made me think and question how I am going to show this experience as it is so invisible. Usually, in a project like this, there is an agenda, but Sarah (Open Eye Gallery) let me do the project how I wanted it which gave me freedom but also it was scary because I didn’t really know what I was going to do. I linked up with Sara (clinical psychologist) from Mersey Care Centre who would tell me about different aspects of dementia. Mersey Care’s main aim in working with me was to raise awareness around dementia and remove some of the stigma. So, I met up with Sara and the group (4 participants) and we decided that we will do short case studies which we would show in a newspaper.

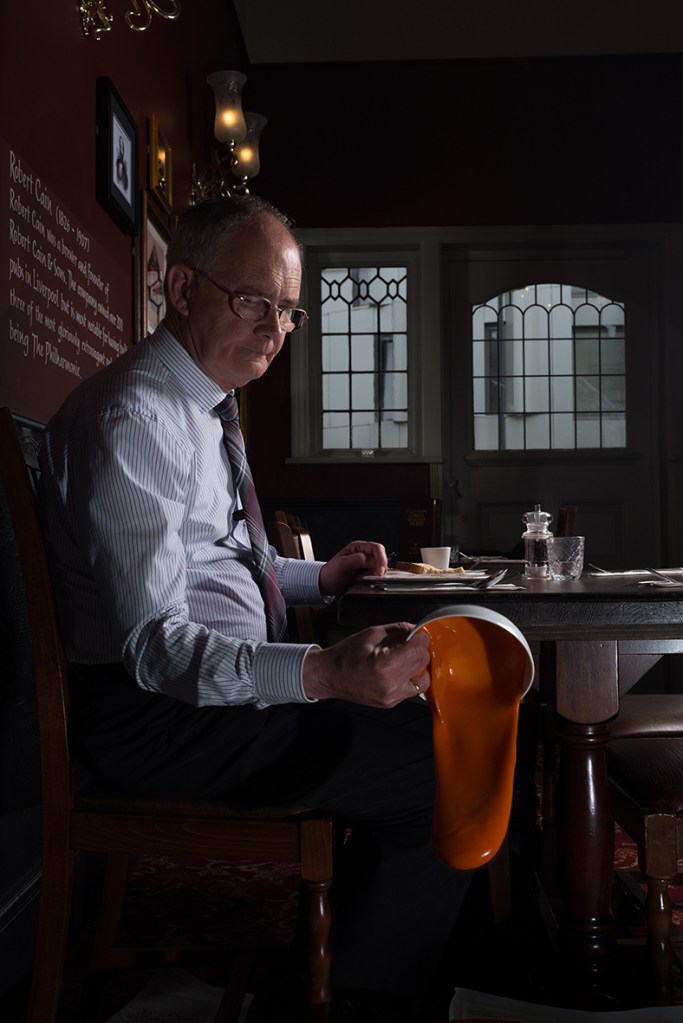

We were trying to contradict the stereotypical image of someone living with dementia, sitting on the edge of a bed by themselves. It’s quite patronising, so rather than portraying it as just a one-dimensional sort of portrayal, include other aspects and reflect on the conversations we had. While Mersey Care wanted a ‘living well with dementia’ look, I didn’t want to create a corporate-looking brochure portraying that everything is fine. I wanted something in the middle showing that there are difficult parts too but that they are individuals. The participants agreed that we should show the reality of the illness and their lived experiences. To get an understanding I would visit Roy (one of the participants), we would have a cup of tea and chat, and then I would come back again and chat with him more. He would try to explain what he is experiencing (looking out the window and seeing a shadow he would see a big hole). Lots of people living with dementia would see that as a gaping hole and would walk around it. And so, he’s talking to me about all these different things. I didn’t know about any of these things and most likely others don’t either. I started including all these different elements in the project. Roy would talk about seeing small animals as hallucinations due to the type of dementia he’s got. The first time it happened he didn’t mention it for over a year as he thought he would be locked up (sent to Rainhill – a psychiatric hospital in Liverpool), then he got the diagnosis. It’s such a big and difficult element of the illness – the diagnosis.

And it took all those visits to earn their trust and listen to the deeper stories. Only after a few visits, I’d take pictures. I was taking some portraits and getting them to reflect on the conversations through the photographs. I was restaging different elements and trying things. It took a while for Roy to develop trust in me and me understanding of him and his situation of living with dementia. He would talk about all sorts of different things and ask questions like ‘Why do I Hoover for 20 minutes, and I don’t even have it plugged in?’ or ‘Why do I put food in the washing machine?’, ‘Why did I pour soup on the floor?’, ‘Why did I do this or that?’. I’d record all the conversations and then listen to them so next time I can ask about some things I heard, like the story of him pouring out his soup. I didn’t really know what he meant at all. Before he was diagnosed, he sat at a restaurant with some other friends and started eating his soup with a fork. A stranger in the restaurant looked at him and said ‘What are you doing? Are you mental?’ and so he poured out the soup just to get out of the situation. Over numerous meetings, he developed more of a trust and would tell me about different aspects he experienced. And I had a thought about restaging this situation to talk about the stigma around dementia. By creating images where it wasn’t obvious that the people have dementia, encouraging others to relate.

Another thing we tried was handing out disposable cameras to the four participants. I asked them to photograph what and when dementia affected their everyday life. Then we came back with all these pictures of cash machines, sweets in the shop, glass revolving doors, doormats etc. They would tell me about the difficulty with the numbers on the cash machine, the reflection on the glass door, and the doormat appearing like a black hole. This was really difficult – and only made sense to me with an explanation. The other thing that everyone knows about dementia is forgetting things. Paul, another participant, always forgot to bring out the camera. Gina went out with her camera but mixed-up cameras for her visit to Edinburgh. That tells another aspect of dementia I suppose. There is an assumption and a saying “If you’ve met one person with dementia, you’ve met one person with dementia” – but soon into the project I realised from those four individuals, that they were all quite different. So, I was trying to think of all the different aspects and how we could show that to people.

Sara – It’s interesting how familiar some things sound, while others are something I never tried or heard of. I think the generalisation is what fuels the stigma and assumptions. And often working with people living with dementia you are not allowed to ask things in case you are upsetting them – but that means that we don’t know their lived experience a lot of the time. Some things you mentioned I can relate to, but others are quite different from my experience working with people living with dementia. We never talked about dementia or asked if our participants had it or what kind. We’d never asked where they were in their dementia journey; we just ignored and kind of talked about whatever they wanted to talk about. So, it’s quite interesting to hear that. I can relate to the long-term trust process, you get to know them, and they open up to you.

Tadhg – I think because I was left to get on with this project, I just approached this quite naturally. The importance of this project is encouraging conversations and informing people of the diverse nature of dementia. I was trying to show some of it through the pictures we took reflecting on lived experience. I realise that the participants didn’t have an idea of what we were doing at the start, they just went along. But then they all felt involved.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

Gina was a massive Beatles fan. Always politically active, she was a member of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament Liverpool movement. There were all these other elements of her that I would learn about through our chats. It took a certain amount of time and visits with her and her family.

Gina spoke about words being difficult and just out of reach which made her frustrated. It’s disconcerting because you know what you want to say but you can’t think of how you say it. The worst thing anybody can do is to say it for you. Once you stop using your vocabulary, you will lose it. If you don’t keep doing things you will stop being able to do them. I had this idea about connecting memory and beautiful old libraries closing due to cuts.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

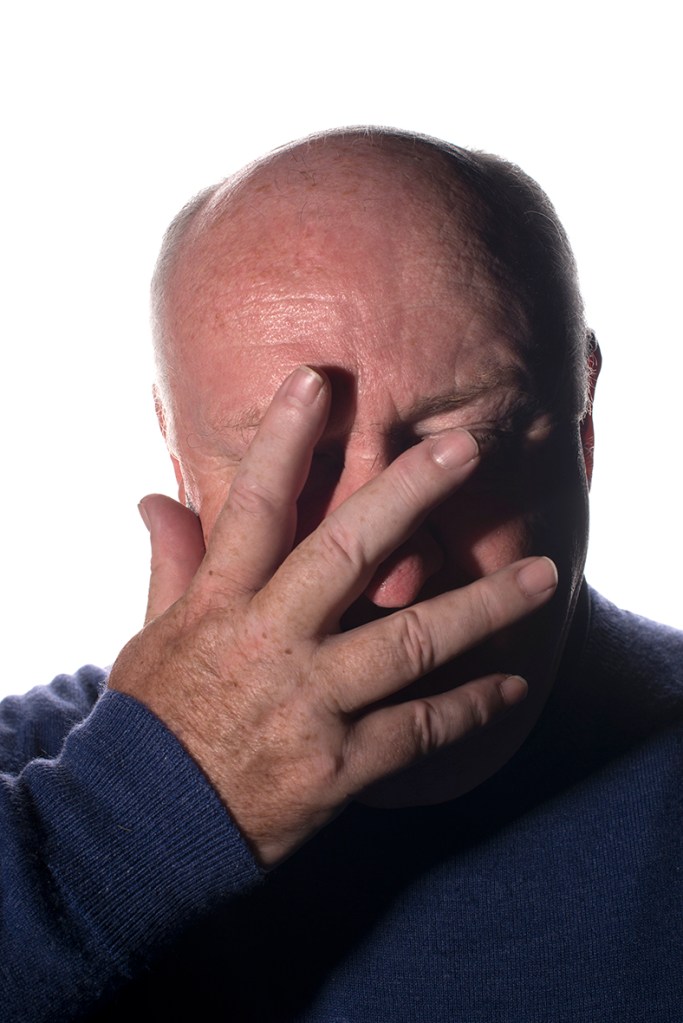

All the words that came out during the interviews were unbelievably powerful. Telling me about what they see or experience and asking, ‘Am I going insane?’, ‘Am I becoming mentally ill?’, ‘Is it only me?’. Of course, it isn’t and it’s not a mental illness. It’s dementia.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

Tommy would say “the biggest thing that you fear is that you’re not able to contribute to society again. I think everyone needs to feel as if they can contribute to society in a meaningful way, not just be a burden on us. When I talk about dementia, I feel as if I’m helping my peers. If I help my peers, I help carers. If I help the carers it takes the stress off them a little maybe. We have got to go out and give messages of hope. And the only way we can do that is by talking positively about having dementia. Feeling useful is such an important thing. A lot of people living with dementia felt that they are not useful when given the diagnosis as from then on, they are meant to sit at home and watch daytime TV to not be a nuisance.”

With this project, I was trying to show the positive aspects but also some of the more difficult aspects. People can relate to it more. If it’s all shiny, it’s not believable. People just dismiss it.

I was trying to hold this balance. Their words are important. They decided what they wanted to do and show, which I think is the most important thing. I was trying to capture as much of them as possible with the words and symbols we used to explain their experiences.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

We did a ‘Walk in their shoes’ tour after the project at Tate Liverpool as part of the Tate Exchange programme. Roy hosted the talk, and we would talk about the photos. We would walk through the gallery, and he would describe the difficulties of going down the steps and going through doors among other things. Paul spoke about his experiences about mixing up money and letters and being misdiagnosed before the dementia diagnosis. Gina also mentioned how talking about dementia and her diagnosis and speaking to others made her feel useful, which helped her move past the diagnosis.

Roy and Stan still meet up with other groups in the UK and talk about the experiences of people living with dementia. Paul went along to one of these meetings and then could talk about his diagnosis.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

Sara – What happened to this project? Is it exhibited somewhere?

Tadhg – The outcome of this project was the newspapers we published. It was a part of the Culture Shifts program at the Open Eye Gallery in Liverpool. Initially, 5000 were printed and distributed throughout Merseyside then we had another 5000 printed. It was designed in a way so it can be taken apart and turned into a temporary exhibition. It is still touring around libraries. I also re-visited and made a video with the original participants of the project last year. Gina wasn’t involved because her dementia has progressed quicker than others and sadly passed away in April 2023.

It also led to the next part of the project where we went into different communities to talk about dementia because in certain communities the stigma is greater. I don’t think I realised the stigma involved at the time. I applied to the Arts Council to be able to work with different communities. I was going to meet different groups but then actually meeting somebody who wanted to talk was difficult.

I have designed a website called ‘Now things make sense’. It’s a quote from a conversation about being diagnosed. So, these are all other projects around dementia that I’ve worked on. There are different elements that are still ongoing.

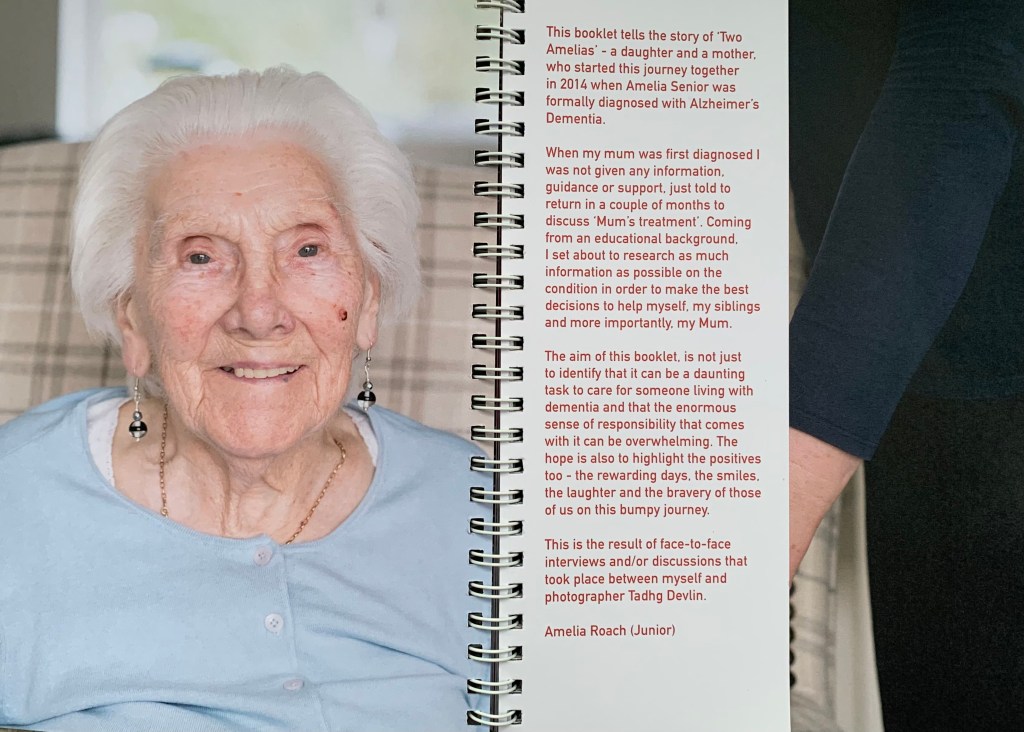

Sara – I really like the booklet of ‘Now things make sense’. It was different pages with colours and sizes indicating how a person’s world is made up. I loved the mixed personal quotes, images, and carers included as well as educational parts. It was a really good combination for me to get a better image of dementia compared to an artwork or just a brochure with a medical explanation.

Tadhg – Thank you!

Continuing from the original project, I applied for Arts Council funding and that was my Amelia project. Amelia & Amelia was a project on Amelia who was the daughter and carer of Amelia. I was asked before to do something about or with carers, so that was what I was hoping to do. I did not realise how hard it would be to find someone who would be happy to be in the project. Being a carer does not give you a lot of free time and it is stressful. It was difficult to get someone to talk about dementia; organisations would agree but people would not. I understand why and respect it, but it took so long to get this project started. I met people in groups who knew someone who knew someone else. I finally found Amelia. She used to work at the college where I work, so there’s this connection. She wanted to tell people about the difficulty of living with dementia and being a carer and all the different aspects. We didn’t know how it was going to work or how we would do it. She had a ‘Tips’ magnet on the fridge and that is where the idea came from for the book. These were reminders for herself. I designed the book. It took numerous tests to figure out the logistics of the layout and design. It takes time to experiment and develop.

Sara – I think the design helped me make it more engaging. If it was a leaflet, I would skim through it and might not even remember much of the content after. But as it is a mix of images, texts, and the smart design I was really intrigued. It felt organised and engaging for my need of learning style.

Tadhg – Thank you! Others said it as well. I’m glad it turned out the way it did.

The Amelia work took a long time, quite a lot of cancellations which delayed the process. Amelia’s mum also passed away in 2020, so she didn’t want to talk about it for over a year. I left it for a while then contacted her again in 2022 and then finalised the book and it was shown at Open Eye Gallery. They showed one of the pictures and included copies of the book. The feedback was incredible. Very appreciative and reflective. People were sharing their experiences, thanking me for showing this, and being emotional by the story.

“Very emotive – Hospital worker. Understood what the photographer was trying to portray.”

“The Amelia guide is beautiful. I lost my nan during COVID to dementia and my father to MSA both needed intensive care. This booklet made me cry, it does a fantastic job of sharing the experience and isolation.”

“Amelia/Amelia guide to care really resonated with me and moved me. A really beautiful and poignant piece of work. I particularly resonated with what Amelia said about ‘living in their reality’.”

“I found both books interesting and insightful, the dementia one is a good guide to coping + caring.”

Sara – Fair comments. People are so kind, and your work is so reflective and authentic, I think it’s much needed for us all to see this! What is the plan with the Amelia project now?

Tadhg – At the moment, it’s touring around libraries in Liverpool. I printed some of the images quite big. We try to get it out there as much as possible for people to see and connect with. Amelia is always really happy about having an impact or making people feel less alone. In the summer (2023) we did a talk in the library. It was a conversation with Amelia and me and the response was just as incredible as the exhibition.

The most recent project I’ve done was working with people’s experiences of COVID. One part of it was about young people living in Malpas, a drama group.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

When we talk about COVID it is often our feeling of being stuck inside and unable to go outside due to the lockdowns. When I was taking the images, I wanted to take the indoors outside to try and turn the world on its head. Again, I think the text was really important. There are also other individuals I worked with on this. It was titled ‘Reflections’. There is a map of those daily walks, objects reflecting on people’s childhoods, being alone in a public space etc.

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

All photographs are displayed with kind permission of the artist ©Tadhg Devlin

Sara – I feel like they are different but they’re also both focusing on human experiences and isolation. Both projects feel like encouragement to talk about this and share what you held in for so long. It’s great.

Tadhg – Yeah. It is quite recent, it was on show at the Open Eye Gallery, a theatre, and a shopping centre in 2023. I always try to create something with a visual interest to engage people and draw them into the story.

Sara – It is quite interesting that there are always physical copies that people can get but you also share them on social media. Which I think offers the projects and their stories to more people.

Tadhg – Yeah, I agree, although it’s quite hard to manage these projects alongside my job and definitely need to do more social media.

Finishing up all these projects made me look at those questions again. It’s also made me look at the other projects as well.

I’ve worked with Open Eye Gallery on certain projects, but I’m also trying to reach out to other people about the work. Maybe people I haven’t worked with in the past. I want to broaden my approaches that go beyond art audiences. There are so many interesting things there’ll be other to me about working with different groups that may not normally work together and I would be the one to try and come up with other ideas and work with them on the visual way of telling those different aspects as well. It’s always quite scary, but exciting as well, because you never know what you’re going to do.